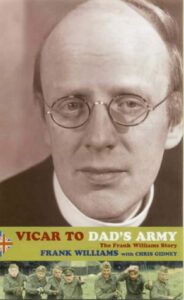

The Frank Williams Story

Frank Williams with Chris Gidney

Canterbury Press, 2002

Frank Williams played the vicar in the TV comedy series Dad’s Army and was later a lay member of the Church of England’s General Synod. He died in June 2022.

As a teenager I used to hate Dad’s Army. I wanted to watch programmes of action and excitement, and all I saw in Dad’s Army was that never much happened and you could often predict what the characters were going to say. As got older, everything I had hated about Dad’s Army became everything I love about it. I have a feeling of warmth for the characters, and when they react in that way you expect them to, it brings a heart-warming smile. Frank writes:

“The characters may be comic but they are also heroic. They care about King and Country, and they really are going to save Britain from the Nazi hordes. Quite often, Captain Mainwaring, in the face of danger and of common sense, behaves with great bravery. […] There is never anything malicious in the comedy, which is perhaps why it has remained so endearing to viewers of every generation.” Pages 180-181.

The Frank Williams of real life comes across as a lovely gentle man. He never has a bad word to say about anyone. However, that can make his autobiography rather dull as no scandals are revealed!

Naturally I was personally most interested in the parts of the book where he writes on Christian matters. As a child he was brought up in the evangelical tradition and then developed a love of anglo-catholic worship. He values the best of both worlds:

“Ardingly College was […] founded in the Anglo-Catholic tradition. ‘I am sure your son will get a good education there,’ I overheard our evangelical rector saying to my father one day. ‘But the religion will be totally, totally wrong.’” Page 30.

“I still believed that a personal relationship with Christ was important, but I also realized that it was important to be part of something bigger. The presence of Christ in the Blessed Sacrament, not dependent on my feelings, but just there, became central to my worship. I began to understand the role of the Saints and the place of the Blessed Virgin Mary. Above all, I came to know that my relationship with God was not dependent on the strength of my faith, but on His Grace. This gave a wonderful sense of freedom and release.” Pages 100-101.

He relates movingly about his mother’s death. Not long before she died, he had been praying for God to heal her:

“thinking about my mother, I sent up a silent prayer for her healing. Immediately an inner voice spoke so clearly that I stopped in my tracks and stood still for a moment. For the Christian death is never a disaster. It is in fact the final and greatest healing of all as the person leaves their illness and all the other trials and tribulations of this life behind and enters into the fuller life in Christ.” Page 108.

Towards the end of the book, Frank recounts his time as a member of General Synod. He was prompted by a conversation with Derek Pattinson who he had first met at a dinner party:

“Derek was the secretary-general of the General Synod. […] One day he suggested that I might like to stand for election to the Synod. I was a bit taken aback. ‘Why would anyone vote for me?’ I asked. ‘I’m not really very well known in the diocese as a whole.’

He was nothing if not honest. ‘You’ve got a face that people will recognize,’ he said. ‘I think you might just scrape in at the last place.’ Page 219.

That is exactly what happened, and he served two subsequent terms with an increased majority. In accord with his nature of always thinking the best of people he describes that in General Synod all were all on the same side – which was not my experience! He does nevertheless accurately summarise the different groups:

“The fact that the debating chamber was circular clearly demonstrated one very important difference from Parliament. There was no sense of a government and an opposition. We were all working together for a common purpose. Clearly there were different viewpoints and groupings within the Synod. The three main groups were: the Open Synod Group, who tended to be those with a fairly liberal attitude; the Evangelical Group, in General Synod affectionately known as ‘EGGS’; and the Catholic Group, which stood for traditional Catholic understanding of doctrine. It was this last group that I was invited to join. I agreed to do so with some misgivings. At the first meeting of the group I confessed to one of my fellow members from London that I did not accept the rather rigid Catholic views on remarriage after divorce. I explained that while I believed in the sanctity of marriage, I felt there were cases when the relationship had irretrievably broken down and it was unhelpful if the Church refused to recognize a subsequent marriage. […] I was greatly relieved when she said that she shared my views. From then on, I happily remained as a member of the Catholic Group throughout my time on the Synod.” Page 222-223.

In the final debate on the ordination of women to the priesthood he describes how the Chair of the debate can bring the debate to a close by reducing the speech limit. When I was on General Synod the most extreme occasion was when the Chair, Dr Christina Baxter, reduced the speech limit to 20 seconds, which rather made a mockery of debate and discernment! Frank writes:

“When I joined the Synod one of the key questions being addressed was the thorny issue of the ordination of women. The Catholic Group took the lead in opposing the measure and I spoke in several debates. I had examined my conscience carefully to be sure that I was not just giving way to prejudice. I had always valued and continued to value the ministry of women, but ordination to the priesthood was a very different matter. I believed there were many arguments against it, but for me the most important one was that it would be very divisive within the Church.

The final vote on the matter came in November 1992. […] To be called to speak in a debate, members had to stand at the end of the previous speech and wait for the chairman to call them. I stood throughout the morning and again throughout the afternoon but neither Archbishop called my name. In matters as important as this, the standing orders stated that the debate could not close while anyone wished to speak. As the hours moved on, His Grace of Canterbury imposed a speech limit of two minutes and then reduced it to one minute. At this point I gave up, feeling that a one-minute intervention would probably make little difference.

[…] when the figures were announced, the motion had been passed in all three houses, the house of laity receiving the necessary majority by only two or three votes.

Clearly the result was an occasion of great rejoicing for the many women who had worked and prayed for this for years. For some of us, at that moment, it seemed like the end of the Church of England. As we left Church House through the throng of people cheering the result, I was near to tears.

The reality of what had happened hit me the following Sunday […] the creed. We came to the line ‘I believe in the Holy Catholic and Apostolic Church’. I did believe in it but felt that what the Synod had done had divorced us from it. Of course it was an over-reaction and I have now come to terms with the decision. It is typical of the Church of England that it made every effort to make it possible for those of my persuasion to stay within the fold. Many good friends, clergy and laity left the Church of England but I have remained, though I still cannot accept the priesthood of women. I deeply value their ministry in all other ways and I have found that with goodwill on both sides it is possible to work things out.” Pages 223-225.

The lasting impression I had from reading his autobiography was that Frank Williams was a very nice man. He is now in his heavenly home.

September 2022

Adrian Vincent