Anthony Jennings

Sacristy Press, 2018

The cover states that this is a “humdinging page-turner of a book”. I found this to be an exaggeration. But it is well written and makes an important point.

Firstly, to explain the terms in the title:

“The words “rectory” and “vicarage” do not, in the strict sense, refer to physical property at all, but to an estate conferring rights and responsibilities. … A presbytery is the Catholic equivalent to a rectory or vicarage, a manse is the Nonconformist version. I therefore use the term “parsonage” as the most accurate term when talking generically about these houses.” (Page xvii).

In 1900 there were about 13,000 parsonages owned by the Church of England. By 2018, more than 12,000 of them had been sold off.

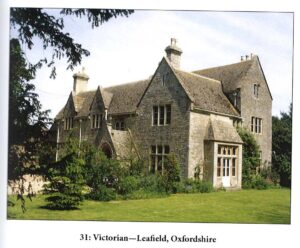

What tends to happen is that they sell off the historic vicarage next-door to the church:

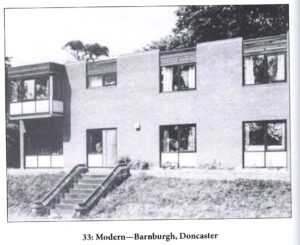

and use most of the money to buy a modern house, further away from the church:

The people who buy the historic vicarage tend to change the name of the house to something like “The Old Rectory” because they don’t want homeless people knocking on the door of the house next to the church, expecting to receive help from a vicar.

Dioceses tend to give various reasons / excuses for selling old vicarages:

“The Church … likes the word “rambling”… when seeking to justify selling a parsonage. Here it implies an impractical house, a house with a lot of wasted space, difficult to maintain and heat, a house quite unsuitable for this day and age, not the sort of house the “modern” clergy could possibly be expected to put up with. Also, a garden which needs mowing every so often, and no busy clergy these days can be expected to mow a lawn. In these times of political correctness, it also means an immodest house, far too large for a mere vicar, a house that gives out quite the wrong signals about the priesthood. It is an extraordinary paradox that while the Church calls traditional parsonages unsuitable, they are the very houses most people want to live in.” (Page 9).

Dioceses sell historic vicarages for a short-term injection of cash. But heritage can only be sold off once, and in the long term it is often a false-economy.

The Victorian vicarage next door to my own church was sold-off by the Diocese about thirty years ago. The reason was given by the Diocese was that it was too large for a vicar and family (even though it had been built for a vicar and family) and too expensive to maintain. A cheaper, modern house was bought for the vicar several roads away. That modern house is now costing the Diocese a couple of hundred thousand pounds in refurbishment to attach exterior insulation to its thin walls and repair the leaking flat roof. Whereas the private owner of the old vicarage has had no trouble with his solidly built old vicarage and is in the process of having an extension built (to a house which the Diocese had said was too large for a family). When the vicarage was next door to the church, people would walk from the church for a confirmation class. That no longer happens when the vicarage is further away.

“Waiting for my wife at a shop in the deepest Lincolnshire fens, I read a notice announcing a coffee morning for the benefit of St Mary’s Church “to be held at the Old Vicarage by kind permission of the owners, Mr and Mrs X”. The Church has to rely on such favours nowadays. (Page 294).

Moving the vicarage to an anonymous house further from the church is a deliberate policy by some Church authorities:

“there is a widespread move to change the role of the clergy. They are encouraged to seek more privacy. Specifically, they are discouraged from having large rooms where parishioners can meet. Parsonage houses are to be perceived as a private domain” (Page 204).

Some rectories had been too large and impractical and perhaps were right to sell off. Then it became an ingrained habit even when it does not make financial sense.

“The book Parsonages: A Design Guide, colloquially known as the “Green Guide”, which lays down recommended specifications, dimensions, configuration, and square footage for parsonages, is a symbol of that centralisation of control. It has become the Bible (if that expression can be pardoned) of diocesan staff. It is advisory, not mandatory, as it expressly states, yet it is widely used by diocesan officers to require an older parsonage of, say, 3,000 sq. ft to be sold, because it exceeds the recommended 2,000.” (Page 211).

“When houses have been sold because they are deemed unsuitable, new ones have had to be built or bought, and the older ones, being in the main much better houses, have become valuable assets in the hands of their private buyers.” (Page 208).

Some rectories have been sold off simply because they are old and don’t fit with a modern church image:

“The bishops and bureaucrats, the Church Commissioners, and much of General Synod alike remain resolutely sceptical of the importance of architecture and history, heritage and tradition, and the part they play in our life. Some take positive pride in that.” (Page 297).

However, tradition and place are good for stability in an unstable world:

“If society has become fragmented, the Church must seek to provide roots, not pander to that fragmentation,” (Page 298).

There could be creative ways to keep a parsonage when there is a vacancy, rather than sell it off:

“at the same time it is telling a parish that the next parsonage is to be sold, the Church is talking about the urgent need for housing for retired clergy. … They may say the parsonages are too big, but houses can be subdivided.” (Page 288).

Jennings makes these important fundamental points, but there is repetition and the book could be slimmed down.

He has lightened the bad news in the book by a chapter entitled “The People” describing various eccentric clergy through the ages. For example, the Revd Sabine Baring-Gould, who was the absent-minded professor type:

“Tales of his eccentricity can be exaggerated, but at a party he bent down and said to a child: “And whose little girl are you?” Bursting into tears, she replied, “Yours, Daddy.” (Page 244).

Adrian Vincent

February 2024