Christian teaching and learning about identity, sexuality, relationships and marriage

Church House Publishing, 2020

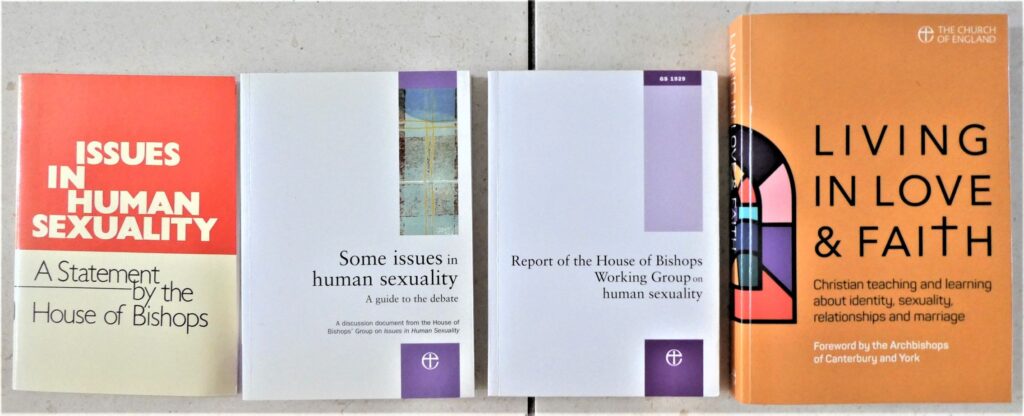

The Church of England has been producing reports on human sexuality for decades. The books tend to get fatter as the years go by:

1991: Issues in Human Sexuality, 48 pages.

2003 Some Issues in Human Sexuality, 358 pages.

2013 Report of the House of Bishops Working Group on Human Sexuality, 203 pages.

2020 Living in Love & Faith, 468 pages, plus course book, website of 16 films, 16 podcasts and numerous essays.

Living in Love & Faith is well written and there is hardly anything to disagree with. The style is ‘some people think X and some people think Y’. It sets out the different positions clearly and fairly.

The length of 468 pages is partly due to repetition. Page 361 gives the game away when it says “as we have noted several times…” The method is to set out the arguments in a chapter, then summarise them at the end of the chapter, then recap them in later chapters.

Despite its length, some of it felt superficial. There are five chapters of “Encounters”, each with headings such as “Meet ESTHER”, “Meet JOSH”, where the life and views of different people are touched on. When I read a one-page summary about someone, I do not consider that I have “met” them.

Another quibble is the overuse of the word “story”. Stories used to be in the Fiction shelves of bookshops, but today it is trendy for celebrities to entitle their autobiographies, “My Story”. Living in Love & Faith uses the word “story” in that sense:

“we are in Christ as embodied, storied and social beings. […] learn how to make sense of these aspects of our own stories in the light of the story of Jesus […]

learn how to break free from the stories that others have told about us or that we have learnt to tell about ourselves – stories that don’t do justice to the gospel […] The story of God’s love for us […] our existence is caught up in that story […] Ours is a story of dying to sin […] It is not a story in which people have to become pure, righteous or perfect before they can be loved by God. It is a story in which God, in Jesus, comes to meet us […] It is a story in which Jesus challenges us […] And it is a story in which Jesus calls and enables us to change […] the story of salvation […] as a love story”. (Pages 206-11).

Some quotes from what I did find helpful.

On identity:

“God affirms us, but God also challenges us to discover and inhabit our identity differently. God sometimes challenges us to let go of things we thought were core to who we are, and sometimes to take on things we had not considered before. But those challenges are never an imposition on our true selves; they are always about being freed from the narrow confines of lives turned in on themselves in order to find our true flourishing with others, and pre-eminently with God. […] there are three aspects of our identity as we now perceive it:

- First, there are aspects that are not only important to us now, but that will also belong to us at the resurrection of the dead and in our eternal life with God.

- Second, there are aspects that may be a proper part of our identity now, but that will no longer define us in the new creation.

- Third, there are aspects that we have to judge as broken or sinful, because they are ultimately incompatible with our true identity in Jesus Christ.” (Page 209 – 210).

On the possible application of passages about Ruth:

“The book of Deuteronomy seems clear: ‘No Ammonite or Moabite shall be admitted to the assembly of the Lord.’ […] (Deuteronomy 23.3-6) […] The book of Ruth on the other hand, is equally clear. Ruth is from the land of Moab, and is regularly called ‘the Moabite’. Yet […] the Israelite Boaz not only shows kindness to her but he also eventually marries her. Through their union Ruth becomes the great grandmother to King David. […] The question then perhaps arises whether, if the law in Deuteronomy 23 is relativized in the book of Ruth, there might be similar relativizing or deprivileging of the Levitical prohibition of same-sex intercourse? Or does the absence of any texts commending what Leviticus condemns challenge such relativization?” (Pages 224-5).

On diversity:

“Scripture also makes provision for and describes patterns of relationship other than marriage as described above; divorce is mentioned and permitted in the law of Moses; imperfect marriages such as David’s and those of many other people of faith do not prevent God’s grace being at work in their lives. […] How do we decide when to accommodate, and when to reject, certain configurations of life? How can this change across times and cultures? And does this create a sense of some relationships only being ‘second best’?” (Page 282).

On love:

“Scripture […] does much more than simply appeal to love, and it does not leave us to fill out for ourselves what love requires. It shows us how to live and love well. […] We need to cover the Bible’s curriculum fully in order to learn what love truly is, hear what the God who is love demands of us, and be led and transformed by the saving and purifying love of God poured into our hearts.” (Page 302).

The Living in Love & Faith process seeks to get away from the stalemate situation in the Church of England of rival camps, one camp trying to push for change, the other camp trying to keep the current doctrine. The idea is to put down our weapons and discuss these matters with no preconceived agenda, learning from each other. It is an excellent project.

However, this truce will not last forever. It seems inevitable that in the next couple of years motions will be put down in General Synod to change the Church of England’s doctrine and practice in this area. The power struggles will then restart, whether it is fighting to retain the traditional church doctrine; or to change it; or fighting to have an ‘agree to differ’ approach of two doctrines.

The two contradictory doctrines approach was recently opted for by the Methodist Church, when on 30 June their Conference voted to authorise Methodist ministers to conduct same-sex marriages in church. They changed their Standing Orders to read,

“Within the Methodist Church this is understood in two ways: that marriage can only be between a man and a woman; that marriage can be between any two people. The Methodist Church affirms both understandings”

I am not looking forward to the power struggles restarting.

Perhaps the missing ingredient is prayer:

“Prayer can take many forms. It can be praise, thanks, confession, lament, contemplation, intercession, and more. Prayer is never, however, a mechanism for generating results. It is not a technique for ensuring the success of our endeavours, or the affirmation of our discernments. That would make prayer a form of trust in ourselves. Prayer, instead, should be a form of our trust in God. In intercession, we pray for, and trust that we will receive, God’s help. We pray for God to guide our reading of the Bible, our engagement with the tradition and with the whole church community, our attention to the natural and cultural world around us, and our wrestling with our own experience. We pray for God to guide our processes of deliberation and argument – and we thank God for whatever help we receive. […] despite all our efforts in this area we still fail. We get things wrong. We fail to convince one another. We misunderstand. […] our prayer is an expression of our dependence upon God, a confession of our failures and inadequacy, and a petition for the grace we need.” (Page 364).

Adrian Vincent. September 2021.