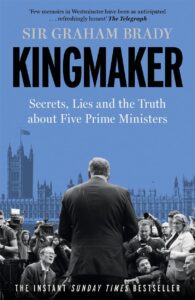

Secrets, Lies and the Truth about Five Prime Ministers

Sir Graham Brady

Ithaka Press, 2024

Graham Brady was elected as a Conservative MP in 1997. From 2010 to 2024 he was Chairman of the 1922 Committee, which represents back-bench Conservative MPs. If 15% of those MPs write Sir Graham a letter saying that they have lost confidence in the party leader, it triggers a vote of confidence.

At the time, Sir Graham never revealed how many letters he had received calling for a vote of confidence. There was a lot of speculation and misinformation about it:

“One problem with the system of using ‘letters’ to trigger a confidence vote is that the numbers must necessarily be kept confidential. In mid-March 2024, Chris Hope of the Telegraph reported ‘a flurry’ of letters, thought to be around 40. In fact, I had received nine. In the first week of April, Sir Simon Clarke briefed the press that ‘around 50 letters are in’. There were still nine.” Page 289.

Irrespective of confidence votes, it was often Sir Graham’s role to tell the Leader that they no longer had sufficient support of MPs and it was time to resign. It is fun to read how he tries to avoid the media by trying different back routes to sneak into Downing Street to tell the Prime Minister that their time is up.

Sir Graham identifies several problems with government and politics today:

Parliament passes too many laws:

“Governments today legislate too much, and often to send a message rather than because they need to. They then produce poor-quality bills which MPs don’t have time to scrutinise and which then turn up in the House of Lords in very bad shape indeed.” Page 30.

MPs are too busy:

“Members are just so busy all the time … They go along to all-party groups, many of which achieve nothing and which seem to be the vanity project of one member who just wants to be seen as the expert MP on one particular cause. They rush from one reception on the Commons terrace to another, with little clear objective. …

They also spend all their time dealing with social media, email campaigns and online petitions. … The public very often rewards the wrong behaviour, too. The MP who spends more time publicising the fact that he or she turned up somewhere and had a photograph taken rather than actually doing anything of substance is often regarded as a wonderful MP. And yet they’ve achieved nothing of value.” Pages 30-31.

Cabinet government is a sham:

“The ‘sofa’ government of the Blair years, where he would make decisions informally with a few trusted ministers, or even just his advisers, before putting his decision to Cabinet as a fait accompli, has become the established norm.” Page 72.

The five Prime Minsters he dealt with were David Cameron (2010-2016), Theresa May (2016-2019), Boris Johnson (2019-2022), Liz Truss (2022) and Rishi Sunak (2022-2024).

William Hague

When Sir Graham was elected in 1997 it was a Labour Government under Tony Blair and William Hague was the Conservative Leader of the Opposition:

“William Hague was an energetic leader whose witty performances at PMQs [Prime Minister’s Questions] did much to maintain morale on the Tory benches through some very difficult years. It was obvious, though, from the result of the 2001 General Election, in which we made a net gain of just one seat, that the public wasn’t listening to us.” Page 39.

David Cameron

Sir Graham has mixed views about David Cameron.

“The people who get to the top job in politics often pursue it relentlessly for years, even decades. David Cameron thought he’d be ‘pretty good at it’ and by and large he was.” Page 287.

He criticises David Cameron for being too smooth, not a conviction politician:

“how little the Cameron camp understood the party … they thought they could use policy as a marketing tool, and then imply that anyone who disagreed with them was automatically undermining the party.” Page 70.

His criticism of all the Prime Ministers he deals is that they don’t want to listen to their back-bench MPs:

“Cameron saw the 1922 Committee: as something that should always back a leader, even when they were getting things wrong.” Page 111.

“I have always believed that all Prime Ministers go mad, and the measure of how good they are is the length of time it takes. I started to worry that Dave was already only hearing what he wanted to hear.” Page 97.

David Cameron pushed forward laws for same-sex marriage despite it not being in the Conservative Party manifesto prior to the election:

“His Equal Marriage plan was annoying some colleagues for religious reasons, but the way it was being sprung on people without being in a manifesto was also annoying people like me, who had no fundamental objection.” Page 108.

Whilst Sir Graham challenged the leader in private, he supported them in public. When David Cameron ‘lost’ the Brexit referendum vote, Sir Graham went on TV to support the Prime Minister:

“the first question was always:

‘Isn’t it now impossible for David Cameron to remain Prime Minister?’

My response was growing increasingly polished by the 19th interview of the morning as I spoke live to BBC TV on the muddy Abingdon Green, opposite the House of Lords:

‘On the contrary, in a time of great change and uncertainty, it is essential that David Cameron should remain Prime Minister, in order to offer stability and direction and to calm the financial markets …’

As I spoke, I saw on the TV monitor in front of my feed David Cameron leaving the front door of Number 10 and walking to a lectern. The subtitle ‘Cameron resigns’ appeared on the screen. A new line was needed! In possibly the swiftest handbrake turn in my broadcasting history, I went on to say:

‘In the new circumstances that we face, it is essential that we move swiftly and seamlessly to ensure that a new Prime Minister is in place to provide the stability and direction that we need and to reassure the markets…'” Page 127.

Theresa May

Sir Graham had mixed views about Theresa May:

“she couldn’t do the people side of politics and she couldn’t deal with a team. But it wasn’t accurate to say that I disliked her; I always admired her unwavering sense of public service.” Page 133.

In order to implement Brexit, Theresa May would need people skills to build a majority to vote for it:

“having lost her overall majority in 2017, she would require good will if she was going to make progress on the central task of securing our withdrawal from the EU. That goodwill was absent.” Page 141.

“Theresa always seemed to regard her colleagues with incomprehension, as though she had not the slightest insight into what motivated their actions.” Page 154.

“she would not accept that she would have to make a concession in order to stand any chance of winning a vote.” Page 158.

The failure of Theresa May to ‘get Brexit done’ led MPs to decide to give Boris Johnson a try:

“Those who thought electing Boris Johnson as leader would always be a risk too far started to think that any risk was now worth taking.” Page 177.

Boris Johnson

Boris had a big victory at the General Election:

“a combination of Boris’s campaigning brio and a widespread fear of Corbyn had propelled the Conservatives to a majority of 80 over Labour.” Page 184.

Then came Covid. Sir Graham was unhappy with all the restrictions the Conservative government enforced, which went against the fundamentals of the party:

“Ministers seemed to have moved seamlessly from a reluctant imposition of extreme measures because we didn’t know how bad the epidemic might be, to thinking they had a right, and perhaps even a responsibility, to keep those restrictions in place until all danger had passed.

This did not sit well with me. People who had spent their whole political lives talking about individual responsibility and about empowering people to take decisions for themselves suddenly thought it entirely natural to remove agency from everyone. I believed that people were able to take some sensible precautions in their own best interests and those of their loved ones” Page 188.

“persistent lockdowns could ultimately kill more people than Covid. We are now experiencing the consequences of undiagnosed and untreated illnesses that could have been found earlier.” Page 199.

Next came the ‘Partygate’ affair, that whilst Boris Johnson was setting all these regulations for social distancing and no social events for the public, he and his staff were ignoring their own rules. When this misconduct was first revealed, Boris’s response made things worse:

“Any communications professional would have advised the PM to get everything out in the open and appear to be in control. Boris, normally an instinctive communicator if nothing else, appeared to do the opposite. He dissembled and withheld information, only to be dragged back to answer questions when more details emerged.” Page 210.

The revelations badly affected the subsequent election campaign. When Sir Graham was campaigning in his constituency:

“I experienced the worst doorstep reaction in 40 years of campaigning. At every house, there was only one topic.

‘I can’t vote for that liar.’

‘How can he take us all for fools?’

‘If I behaved like that at work, I’d be struck off!'” Page 213.

“another party donor for many years who told me he couldn’t give any more while we had a ‘man with no moral compass’ as leader.” Page 225.

Boris frequently apologised, but no one really believed him:

“Boris came to the ’22 that evening and attempted his best impression of contrition.” Page 216.

Liz Truss

Sir Graham doesn’t have much good to say about Liz Truss, whose time as Prime Minister lasted only 49 days:

“I had always found her somewhat peculiar … She had a reputation among my colleagues for being an adventurous risk-taker and she certainly exuded a strange kind of energy in person” Page 241.

She had appointed a cabinet of only her own clique. When her budget went wrong and had to be reversed, she didn’t have the wide support of her MPs:

“the One Nation side of the party, having been almost completely excluded from ministerial office under the new administration, felt no obligation whatsoever to defend the Truss government – it wasn’t theirs. It was a government by a faction, not by a party.” Page 251.

Kwasi Kwateng was her Chancellor who had introduced her economic plan that had gone so badly. In an attempt to save herself, she blamed Mr Kwateng and sacked him:

“The BBC reported his sacking before he knew about it.” Page 255.

“She told me that Kwasi had let her down and that she was now dealing with his mistakes. We discussed whether it would be possible for her to survive.

I … explained that the parliamentary party seemed to be in three more or less equal groups: a third wanted her to go immediately; a third wanted her to go when we knew who to replace her with, and a third will always support the leader whoever it may be. Things would become untenable once the middle third joined the first.” Page 258.

Rishi Sunak

Sir Graham has more respect for Rishi Sunak, as a competent and steady leader:

“It is easy to underestimate how much people want stability and how unsettling they find too much change. Easier still to forget that when in Westminster. … Unfortunately, many are attracted to this place because they like the drama.” Page 271.

“not only is Rishi Sunak decent and competent, he also has rather less ego than is normal for a senior politician. Attacks on Sunak for his wealth – suggesting it made him ‘out of touch’ – couldn’t have been more wrong. Those who have dealt with Rishi find him surprisingly normal.” Page 286.

Rishi Sunak achieved an improvement to the Brexit arrangements:

“the Windsor Framework was going to mark a big step forward for the post-Brexit arrangements at the Irish border. It embodies some of the common sense ‘work-arounds’ that should have been there from the start. …

Diligence, steadiness and a bit of charm had allowed Rishi to achieve what his predecessors had not.” Page 283.

When the General Election came, people were fed up with the Conservatives. Two years of relative stability under Sunak wasn’t enough to win an election.

February 2025

Adrian Vincent